This past weekend, the Washington Post ran a story about painter and photographer Richard Prince, whose slightly-reconfigured blowups of Instagram users’ photos were recently shown (and sold) at The Frieze Art Fair in New York–for a cool $90,000 each.

The focus of the Post article was on ownership of the Instagram photos themselves, and the flexibility of copyright laws related to images. But it’s not just ownership we need to think about with images; it’s the challenge of interpreting what they mean, so we can determine what action to take, if any. Some use cases include:

- Image-based UGC/Native advertising

- Content marketing

- eCommerce (increasing lift)

- Risk management (copyright)

- Risk management (brand)

The Emerging Science of Photo Analytics

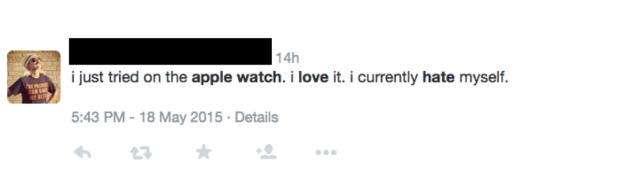

When we think about understanding “the customer’s voice” through social media, we generally think about text. A tweet such as this one presents a few interesting challenges for a human (not to mention a machine) to interpret; the sentiment is mixed (love the watch, hate myself), the person may or may not be an owner (did he buy it?), and there isn’t really much other behavioral data (he tried one on and wrote about it) to interpret.

Beyond that, we can look at the metadata to try to determine whether and how much it was shared, the profile of the poster, and so on. But these 14 words don’t tell us a whole lot; a listening tool will tell us that it is a brand mention, in English, with mixed (not neutral!) sentiment. That’s not a bad thing; it simply illustrates the challenges that we–not to mention machines–have with the 140-character format, and with human language as a whole.

Contrast the above with something like this image I found on Flickr:

A human can detect that the focus of the photo is a butterfly-shaped object that started its life as a can of soda. A photo analytics tool such as Ditto could likely detect that it contains a partial Coca-Cola logo. If it were shared in Instagram or Pinterest, and contained enough useful metadata, Piqora might return it in a list of search results.

But the real question, if I’m a brand marketer at Coke, is this: what do I do now?

- Is it a brand mention?

- Is it positive or negative?

- Can I tell the identity of the poster?

- Is that person the same as the creator of the image? Of the butterfly?

- How else do I categorize it?

- Can I use it in native advertising, commerce or other types of campaigns?

- Is it a brand risk?

- Is it actionable in other some way?

This is particularly critical as brands incorporate user-generated content into campaigns, and as automated campaigns become more popular. In February Coke launched, then pulled, their online #makeithappy campaign when a user added the hashtag to a tweet containing white supremacist content. Gawker then created a Twitter bot to test whether it could make the account inadvertently tweet lines from Hitler’s Mein Kampf. Short answer: it could, and it did, and Coke shut down the campaign immediately.

This is where brands must balance optimism with sometimes harsh reality: optimism that involving the community can be beneficial, and the reality that someone, somewhere will appropriate that content for their own uses: artistic, competitive, financial, political, comic, or just plain nasty. Clearly, malicious intent is more of an issue on some platforms than others. Instagram and Pinterest tend to be, as Sharad Verma, CEO of Piquora says, “happy platforms.” Twitter and others tend to have more problems with abusive content, as has been widely reported.

As you can imagine, it would be fairly easy to get lost in analysis paralysis with digital images, especially since we are still so new at the science of understanding and using them. So let’s start with a few basic principles:

- Images are brand mentions

- The science involved in interpreting them is still very new. The main approaches focus on interpreting the image itself, the metadata associated with it, or a combination (ideally) of both.

- A few things are possible today with image recognition: logo identification and some (very basic) sentiment analysis. Given metadata, search becomes more feasible and useful.

- Popular social platforms such as Instagram, Tumblr, Snapchat (and others yet to be invented) are highly image-centric.

- Images are more universal than language, though there are always exceptions

- Automated campaigns will always hold some element of risk if they use or even simply suggest the use of UGC.

- You’re going to need to figure this out sooner rather than later, because GIFs, video, spherical video (coming from Facebook), augmented reality and virtual reality are here, and they’re going to be a lot more complex from an analytical point of view.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on use of images and image analytics; what you’re using, looking at, thinking about, terrified of and excited about.

Pingback: Seeing through the customer's eyes: the emergin...